Cop City is already hurting Disabled people

If you are unfamiliar with the movement to Stop Cop City or don’t know what Cop City is, start here. For more detailed, further reading, please see Micah Herskind’s article on Scalawag.

The first time I found myself in Weelaunee People’s Park, I didn’t know it by that name. There wasn’t yet a clear consensus on how to enter the forest, and, going off of a map being passed around in a Signal chat, one balmy evening in summer 2021 I walked three miles along a service road with huge metal towers and wires dipping across the landscape. I climbed over a dirt berm that seemed to be where trucks entered the forest, and walked another half-mile of winding trail, passing a pond. Wooden boards were laid over dirt craters filled with rainwater, the huge puddles I had seen pictures of my friends traversing at a rave a few nights before. Eventually, I came to where a few tents and tarps had been set up to create a campsite. I was there to celebrate the Jewish Sabbath with some friends I hadn’t seen since the first few months of 2020.

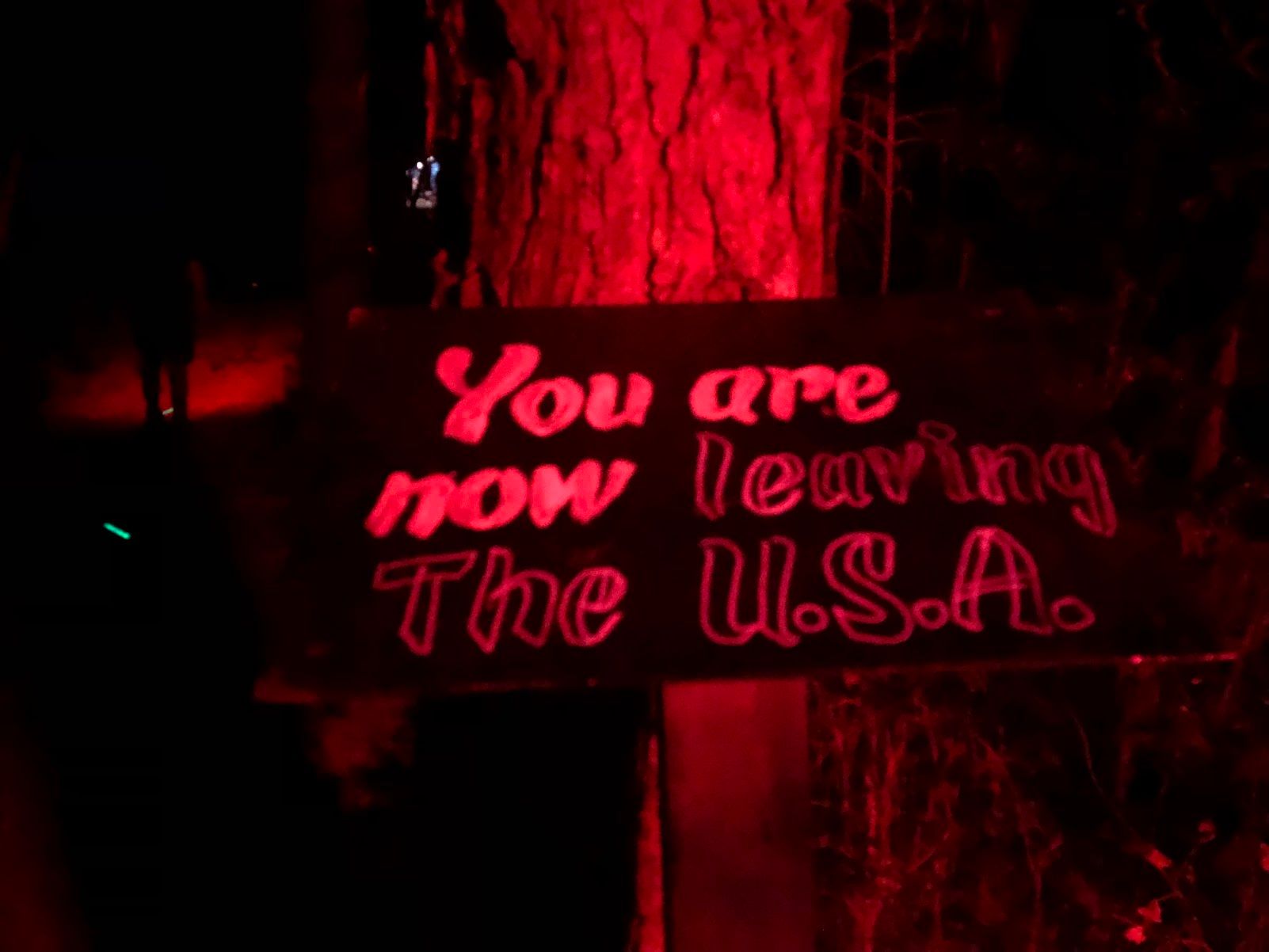

People were sitting in a circle on the ground, talking about who was coming into the camp and what they were bringing. “Does anyone mind if I take my shirt off?” my friend asked, and we all murmured no’s, and she pulled her t-shirt off and laid back with her bare shoulder blades to the dirt, looking up at the tree canopy. People started talking about flora-and-fauna-based nicknames to go by. “My forest name,” they were saying, “Here we go by our forest names.” It felt almost joking at the time, but the tradition became more real as the struggle went on, taking on real usefulness in both concealing one’s identity as well as solidifying the forest as a separate space. Echoing other autonomous zones erected during recent protests, a sign once was displayed in the entryway to the forest that read, “You are now leaving the U.S.A.” Although we were only a few miles into the woods, the city felt imperceptible and out of reach. In death, forest defender Manuel Terán is now known mostly by their forest name, Tortuguita.

At this point, it feels like everything there is to say about Cop City has already been said. It’s hard to imagine that I would draw up a new point that hasn’t been stated in seventeen hours of virtual public comment, seven hours of in-person public comment, in nearly every major national news publication as well as international coverage, in EAV bar bathrooms, in a zine, wheat-pasted on electrical poles, in spraypaint on shattered pavement, in the shell of a burnt-out construction vehicle, at a candlelit altar for Tortuguita, in a bouncy house, on a rave dance floor, or on a flyer disseminated in a public park.

In some circles, Atlanta has actually started to become synonymous with the Cop City struggle – touring musicians like Bikini Kill and Laura Jane Grace have spoken out against it on Atlanta tour stops, metro Atlanta locals the Indigo Girls have expressed their dissent, novelists Richard Powers and Margaret Atwood, and activists Angela Davis and Bernice A. King have spoken out against the building of Cop City. Finally, this week, Democratic darlings Ossoff and Warnock have finally made vague statements about the movement on Twitter, likely due to the Solidarity Fund arrests and due to some brave graduates at Bard College’s commencement last week.

One of the most unique and astonishing aspects that newcomers to the Cop City struggle often comment on is how wide-ranging the issue is, and how it affects nearly every marginalized group. To lay it out plainly:

Cop City is intended to be built in a predominantly Black neighborhood, within earshot of a juvenile detention center, where already vulnerable minors and their neighbors would be subjected to the sound of bombs and gunfire during training sessions, and within walking distance of a high school.

The building of Cop City would worsen the already rampant gentrification and economic inequality in the city of Atlanta by displacing residents.

The cops being trained at this facility would, of course, be policing the Black and Brown communities of Atlanta. Specifically, they train with a program called GILEE, where Georgia police officers learn from Israeli officers, training with the same tactics used to oppress people in occupied Palestine.

The proposed training facility would be built on occupied Muscogee land, the area they called Weelaunee, or “brown water.”

The facility would also lie on the remains of the Old Atlanta Prison Farm (a Jim-Crow-era forced labor camp) and on the remains of a 19th-century slave plantation.

Tortuguita was an Indigenous, queer, nonbinary person. They are considered to be the first climate activist in the U.S. to be murdered by the police during a protest.

Atlanta is considered an LGBTQ+ safe haven. Cop City would put Atlanta's queer community at higher risk of police violence.

The destruction of the forest would hasten the climate emergency in the city of Atlanta. The resulting pollution from deforestation and “practice rounds” of chemical warfare would harm Atlantans with existing respiratory issues and sicken more. Asthma rates are already higher in South Atlanta (where the facility would be located) than in the rest of the city, and that’s not even considering the now-existing respiratory damage from COVID.

Furthermore, Cop City is not a local struggle. If Cop City were to be built, it would serve as a criterion for what other metropolitan police forces feel they are at liberty to do. At over 85 acres and costing at least 90 million dollars, it would also be the largest police training facility in the United States, setting a precedent for police budgets across the country.

So you can imagine the kind of pressure we are under to stop this project.

On the morning of May 31, the intentional community in Edgewood known as The Teardown was raided by heavily armed officers. Three activists were arrested, including a Disabled person who was kept in solitary confinement, denied their medication, and had their medical equipment taken away. The three activists who run the Atlanta Solidarity Fund, an organization that provides funds for bailing political protestors out of jail, were charged with charity fraud and money laundering.

The inhumane conditions of DeKalb County Jail have been well-recorded at this point, and the jail specifically has a history of withholding medical care, medications, and dietary needs from inmates. While the Solidarity Fund activists were thankfully released on bail (a small charge of $15,000 per person), the message was clear: if you oppose this project, you are liable to have a SWAT team raid your house and throw you in jail, and if you’re Disabled, you’ll be left to collapse or seize or enter psychosis or whatever it is that y’all disabled folks do, and you can do that unmedicated and entirely alone.

Hannah Grim, who was arrested on bogus domestic terrorism charges at the South River music festival and incarcerated in the DeKalb County Jail for 31 days, wrote that “the state of Georgia does not run county jails—it runs concentration camps that it calls county jails.” Grim wrote that mentally ill detainees could often be heard screaming from their cells while on 24/7 lockdown and that the jail was kept below 60 degrees Fahrenheit at all times. Grim’s cellmate had been held in solitary confinement for seven months due to medical pregnancy complications. (Solitary confinement that lasts more than fifteen consecutive days is considered by the United Nations to be a form of torture.) Grim recounts a guard’s laughter after seeing an inmate attempt suicide with a tied bedsheet.

To support Cop City is to facilitate more of this treatment of human beings.

When the Atlanta Police Foundation’s construction goons smashed the paved walkway in Weelaunee People’s Park and destroyed the gazebo that served as a mutual aid station, they eliminated access to the park for wheelchair users, people with strollers, people on bikes, and people with broader mobility issues, as the shards of concrete and the resulting erosion of the soil were not particularly comfortable or safe to walk on. Of course, they soon eliminated access by any members of the public, but they made it ADA inaccessible first. Despite our best efforts, APF and their construction team have already illegally and clandestinely clear-cut a large amount of old-growth forest.

To say that Atlanta takes pride in its tree canopy would be an understatement. It’s known as “the city in the forest”; in fact, in 2017, the city government themselves referred to the South River Forest (Weelaunee) as the “lungs” of Atlanta. As my friend C said at a recent Jewish anarchist event, all of Atlanta is connected to the forest. “If you live in Atlanta, you live in the forest.” I want to extend that more broadly: wherever you might live, if you care about this movement, if you understand its significance, and if you are ready to stop it – you are a forest defender.

I went to church on Sunday; that is, I went spontaneously to the Park Avenue Baptist Church on Sunday evening. It was my first time, and after trekking up steep, crumbling concrete stairs, I was welcomed into a sanctuary decorated with children’s drawings of the forest that said “We are nature defending itself,” and a beautiful painting of a turtle’s back, and no crosses or images of Jesus anywhere prominent. We sang labor movement protest songs, and ate pizza, and listened to poetry, and someone lectured a history of the transatlantic slave trade from memory. Tortuguita was lovingly acknowledged often.

It was all to provide support ahead of the June 5 Atlanta City Council meeting, where, after however many hours of passionate public comment, the City Council will vote on whether to provide the city’s $30 million portion of funding for Cop City.

In the lobby of the church, I met M. and told them I felt a little nervous about the outcome of the city council meeting. M. has a gorgeous afro like a young Angela Davis and was wearing a sweatshirt that read “union thug.”

M. looked me in the eyes and said, “No matter what happens tomorrow, we’re going to win.”

Somehow, I believe them.

![[substack archives] puresound letter 002: remembering everyone](/content/images/size/w750/2021/05/puresound-002.png)

![[substack archives] puresound 001: pride month forever](/content/images/size/w750/2021/05/https___bucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com_public_images_2d371990-9fb9-47b8-8a18-035229ee30d4_1000x667.jpeg)